It is widely used in fields such as medicine, psychology, social sciences, and public policy, where evidence-based conclusions are critical for advancing knowledge and informing decision-making.

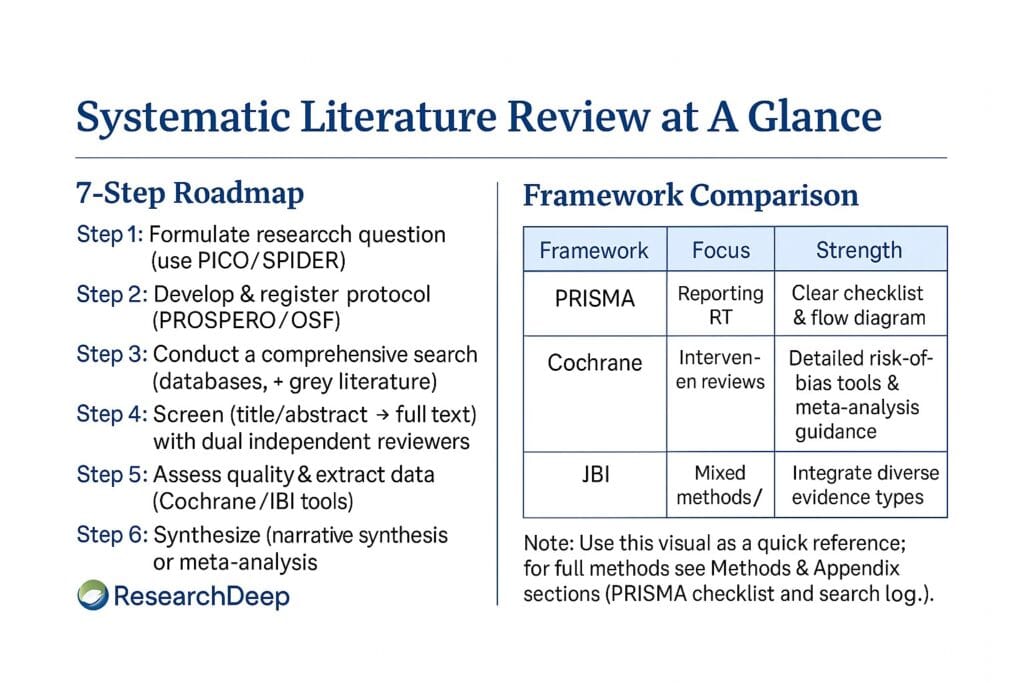

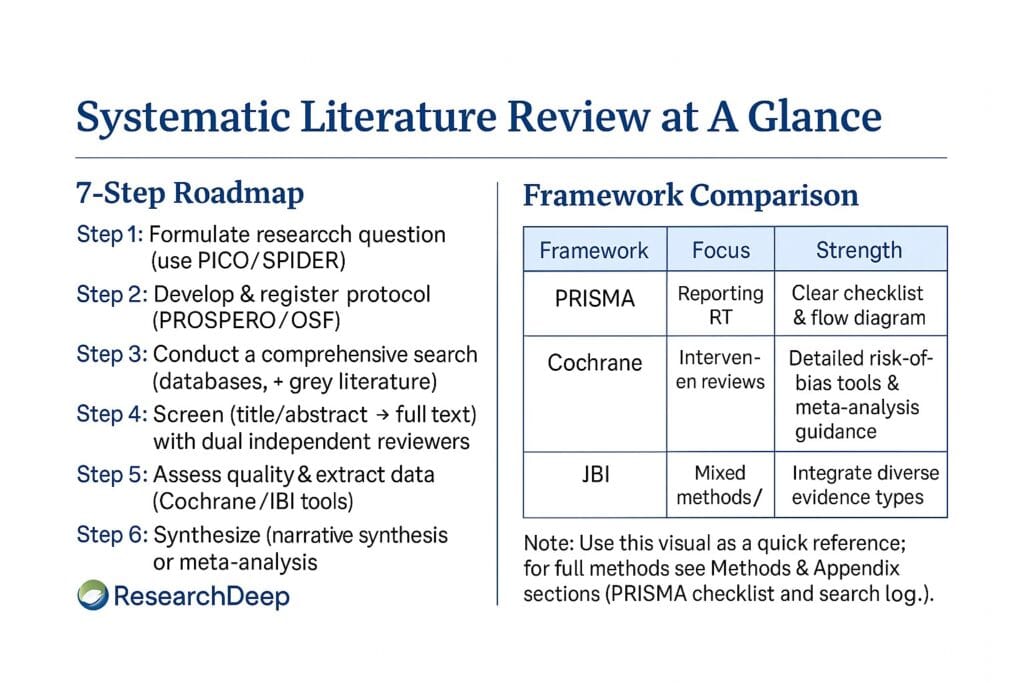

By adhering to frameworks such as PRISMA, Cochrane, and JBI, scholars can ensure their reviews meet the highest standards of transparency, rigor, and reproducibility.

Every systematic literature review begins with a well-defined, good research question. A straightforward research question shapes your search strategy, inclusion criteria, and analysis.

A standard tool used in this context is the PICO framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome), particularly in the health and social sciences (Richardson et al., 1995).

Example:

Beyond PICO, frameworks such as SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) are used in qualitative research.

Tip: Form a multidisciplinary team. Involving multiple reviewers from diverse backgrounds enhances objectivity and minimizes selection bias (Liberati et al., 2009).

A protocol is the blueprint for your systematic review — it defines your objectives, inclusion/exclusion criteria, search strategy, and data extraction methods. Writing it beforehand ensures rigor and transparency (Higgins et al., 2022).

Key Actions:

Why this matters: Registration prevents duplication and allows the research community to validate your methodology (Moher et al., 2015).

The literature search is at the heart of your SLR. It ensures comprehensive coverage of all relevant studies and minimizes publication bias.

Steps to follow:

Please keep a record of your search terms, databases, and the dates you used them. This transparency allows replication and supports reproducibility.

After gathering your sources, you must systematically screen and filter studies to determine eligibility.

Two-phase process:

Use tools such as Rayyan, Covidence, or DistillerSR for efficient dual screening. Maintain a PRISMA flow diagram to record inclusions, exclusions, and reasons for exclusion (Page et al., 2021).

Tip: Two independent reviewers should screen all studies to minimize bias.

Assessing methodological quality ensures that only reliable evidence informs your synthesis.

Quality Assessment Tools:

Create a standardized data extraction sheet (e.g., Excel or Covidence) to record:

Perform data extraction independently by at least two reviewers for consistency (Higgins et al., 2022).

Used when data are heterogeneous. Identify themes, research gaps, and contradictions across studies through thematic or narrative synthesis.

When data are homogeneous, use statistical methods to combine effect sizes and compute pooled estimates. Software like RevMan, R (meta package), or Comprehensive Meta-Analysis can be employed.

Highlight inconsistencies and perform sensitivity analyses to evaluate robustness.

Your final step is to report, interpret, and discuss findings transparently.

Structure your report:

Follow the PRISMA 2020 reporting checklist (Page et al., 2021). Mention any biases, publication gaps, and methodological weaknesses.

| Framework | Primary Domain | Key Document | Key Strength | DOI Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRISMA (2020) | Multidisciplinary | Page et al. (2021) | Transparent reporting | 10.1136/bmj.n71 |

| Cochrane Handbook | Health Sciences | Higgins et al. (2022) | Rigorous risk of bias tools | 10.1002/9781119536604 |

| JBI Manual | Mixed/Qualitative | Aromataris & Munn (2020) | Integration of diverse designs | 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01 |

A systematic review follows a defined, reproducible protocol, while a narrative review is more interpretative and less structured (Grant & Booth, 2009).

Depending on the scope and team size, it may take 6–12 months, or sometimes longer, for meta-analyses (Borah et al., 2017).

Yes. Tools like ChatGPT, Rayyan, and ASReview can assist in screening and summarizing, but must be verified for accuracy.

No. A meta-analysis is only feasible when data are sufficiently comparable across studies (Higgins et al., 2022).

A systematic literature review is one of the most robust methods for evidence synthesis, valued for its transparency and reproducibility. By following frameworks such as PRISMA, Cochrane, and JBI, researchers ensure their findings are comprehensive, verifiable, and impactful.

When done rigorously, an SLR not only summarizes the current state of knowledge but also highlights gaps that guide future research directions — a cornerstone of scholarly inquiry at the master’s and PhD level.

Adams, R. J., Smart, P., & Huff, A. S. (2017). Shades of grey: Guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(4), 432–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12102

Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (Eds.). (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

Borah, R., Brown, A. W., Capers, P. L., & Kaiser, K. A. (2017). Analysis of the time and workers needed to conduct systematic reviews of medical interventions using data from the PROSPERO registry. BMJ Open, 7(2), e012545. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012545

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2022). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), A12–A13.